Before I knew anything about trauma and before the word was loaded with cultural references and nervous system terminology, I knew about suffering.

These days, trauma is so much a part of our social landscape that the teenagers in my house throw around the term casually, and many a minor inconvenience prompts declarations like, “I’m so traumatised,” and “I have PTSD,” or even “amygdala overload.”

TikTok, am I right?

My clients who have actually suffered undeniable childhood trauma, the kind we don’t talk about in polite company because it’s horrific, often show up to sessions already having read seminal works. They know about their dysregulated nervous systems. They’ve read Bessel van der Kolk and Peter Levine; they know about the vagus nerve and Stephen Porges. They’ve binge watched Gabor Maté.

Of course, thank you to all these trailblazers who have made my life easier as a practitioner. Understanding is part of healing, and it’s great to know that the nervous system is behaving in ways that are distressing for very sound reasons. Yet this trauma-informed world we live in is new, and I can’t help but reflect that before I even knew about trauma, I knew about suffering, and all these years later, it’s my experience with suffering that has most influenced both my spiritual path and my relationship with trauma.

Suffering

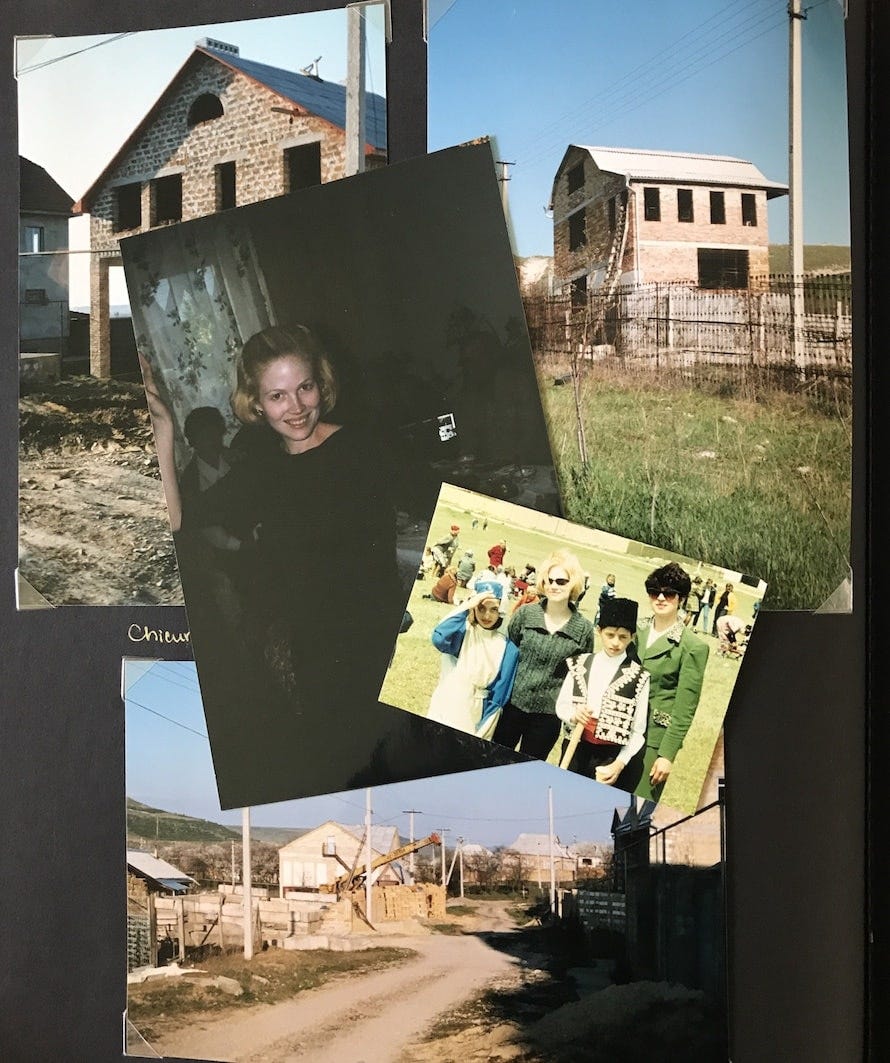

Twenty-four years ago, I did research for my doctoral thesis in Crimea, in a settlement camp where Crimean Tatars were squatting illegally and suffering in most ways you can imagine. These were people who had experienced genocide just one generation earlier. That was back in the year 2000. No one was throwing around words about trauma then. But the suffering was all too real, and I was just a 26-year-old doctoral student with no therapeutic tools to offer.

The Crimean Tatars had been deported en masse by Stalin in 1944 from their homeland in Crimea to Central Asia. Most perished. Then in the late 90’s with the fall of the Soviet Union, after having advocated peacefully for decades, they were finally granted the right to return to their homeland. Return they did. Only they were not recognized as legal citizens in what was then Ukraine, and so they found themselves illegally squatting in homes that ranged from lean-tos to semi built structures. Many were ill with blood diseases like leukemia.

As I interviewed these returnees for my doctoral thesis - which was incidentally about economics, non-violent protest and political structures - not about suffering at all, I listened to story after story of loss. Losing homes, losing family members, losing a culture and an identity. One woman, a proud matriarch with four sons, had lost her husband to throat cancer. Without medical care or access to pain relief, he died in excruciating pain of starvation, unable to swallow. I remember her fiery eyes and robust self-assurance. I wondered about the depth of her experiences. I wondered what feelings she navigated as she raised her children. I wondered how I would handle it, if it were me in her place.

I often say that my experience in Crimea was the beginning of my lifelong interest in human suffering, but it only became a speciality in trauma when that was a word we were all using to understand experiences of suffering which led to PTSD and complex PTSD and so on.

I began to work as a practitioner after a career change that came following years of motherhood and my own traumatic divorce and subsequent breakdowns. Even before I did any formal study or saw a single client, I had an understanding of what trauma was, so when the concept was introduced in my initial training, which was Shamanic de-armouring, I already felt familiar with its permutations.

I didn’t have to look hard to find within myself a conceptual container for making sense of trauma. The girl who had cancer when I was just a child. The childhood friend sexually abused by her neighbor. My best friend’s father who at the age of 17 whilst serving in Vietnam, watched his best friend be blown up and then came home to drink the rest of his life away. Several female friends who lost their babies at birth. My own marriage ending, and the reemergence of my childhood wounds.

I thought back to the refugees in Crimea, during my doctoral research.

Obviously, suffering, and that includes trauma, is inherent to the human condition.

Suffering is the oldest human story known to man. It is one of Buddha’s first precepts, that life is suffering. And once you experience it firsthand, you can’t unknow its ubiquity. So what does suffering teach us, that the modern framework of trauma doesn’t?

Back to my doctoral research in Crimea.

Compassion

I had seen suffering before, as mentioned above in my teenage years, but I had no training as a practitioner. The only ballast I had in those turbulent waters was my spirituality. I was already meditating in my 20s, already had experienced some pretty amazing connection with the Divine, with consciousness, and it’s fair to say that I was consciously desiring a deeper experience of my own spiritual nature.

So as I listened to nearly 100 personal stories of pain in my months in the settlement camps, with my simplistic understanding that to be human was to suffer and to suffer was to be human, I offered loving presence. I bore witness. In the silent spaces between breathless pain stories, I attempted silently to transmit whatever joy, love, or hope I could muster.

So it was that in that settlement camp, I sat in my compassion, receiving pain and offering love. This practice informed everything that I became and everything I did after, after I learned the right terminology, after I understood dysregulation and the vagus nerve and fight or flight, after I amassed a therapeutic toolkit.

Compassion is unique in its heart-centred transmission. It is a form of love offered to an equal who is is suffering.

Pity looks down at the other as if from a higher place. Empathy requires lowering oneself to the other, to suffer alongside someone. I disagree with the common dictionary definitions of compassion, which place it closer to pity (com + passion = to suffer with).

I align more with the Buddhist view, which recognizes our equality as souls, and understands that extending compassion is an active practice which connects hearts for a living exchange of healing energy. The Buddhist tonglen meditation is a transmission of giving and receiving; first, to oneself, by breathing in our own pain and suffering as a way to lean in and not resist, then breathing out joy, peace, and light.

But tonglen is also about being present with someone else’s pain, and breathing that into our being, receiving it, then breathing out whatever joy, love, or lightness we have as a way of transmitting compassion to the other. Taking in their suffering, and transmuting it through our very being.

I didn’t know any of this as a young doctoral student, but my instinct was aligned, and despite all I’ve seen since, I rest most comfortably in this view of offering compassion as the key to profound change.

Healing, Trauma, Compassion

These past few years, my new clients appear with an often nuanced understanding of the somatic dimensions of their trauma, yet, all too often they are unable to extend to oneself compassion and self love. Usually this omission is not even on the radar, which is normal when the people who are supposed to role-model compassion (parents) were abusive, neglectful or absent altogether. So, self-compassion must be taught.

Healing is hastened by the cultivation of self-compassion.

I know this in practice. There are a many therapeutic tools that reduce trauma symptoms, but the experiential dimension of compassion offered and received by the sufferer is what animates the tool. Content trumps form every time.

Yet even more unfolds when compassion settles into a way of being beyond a momentary self-soothing practice. Compassion is, as I noted before, a form of love and after it takes root, it flowers into other forms of love: love of others, love for life, or more generically a pulsating, radiating experience of love.

You might say that love, being the very nature of the Divine, magnetizes like to like, and so in experiencing love, our consciousness opens us to deep connection with all beings and by extension, to the Divine. This is the intention behind tonglen, to awaken our sense of kinship with our fellow humans, and in knowing our oneness, to open our hearts and minds to oneness in general (that is, non dualism, our ultimate unity in consciousness).

The spiritual teacher Saddhguru has said that there are many roads to enlightenment, but the one thing that can cut through anything else and facilitate awakening the fastest is love.

Compassion for self and others, due to its love-nature, can initiate a path back to Wholeness, facilitating profound healing along the way.

I see compassion as the bridge between growing up and waking up, because it is a way of being that serves both our ego, human selves (who want to grow up and out of pain stories), as well as our souls.

Thank you for reading. xx

*note ~ I’m going to expand on this in an upcoming podcast, with some practical examples and practices.

For those who are interested in learning how to work with me, you can visit me here: michelle-dixon.com

Love this. 🙏🏻🙏🏻